Blackfish serves more as a confessional for its past trainers and ringmasters to let it all out than it does to highlight the sad state of marine life under SeaWorld’s care. The film purports to be an expose on the treatment of animals kept in captivity but the narrative quickly shifts its focus onto the people involved in that industry.

The documentary makes an easy argument: Tilikum, an orca, has been involved in the death of three people, and the producers posit the very plausible idea that the shanghaiing of these animals coupled with the forced separation from their offspring and the subsequent less-than-adequate living conditions have occasioned a sort of aggressive psychosis.

The case is prosecuted with a mixture of mystical anthropomorphisation that any savvy SeaWorld lawyer could probably have pointed at when constructing their defence and, altogether more damning, a cataloguing of the physiological effects of captivity on these great beasts including the poorly understood phenomenon of dorsal fin collapse, a much reduced lifespan and aggression caused by other captive orcas.

Of course, by the time SeaWorld has been caught out in some rather unseemly lies, the most heinous of which is the attempt to explain away the last death, that of trainer, Dawn Brancheau, as “error” on her part, it has well and truly lost the argument, the moral high ground and, with any luck, some of its ticket sales.

But what have we really learned about the issue of animals kept in captivity ostensibly for research but more often than not for entertainment? This is where the interrogation of the industry falls apart, and where the documentary fails.

“Can you imagine a world without SeaWorld?” – or something equally insipid – asks one of the few SeaWorld supporters. Well, yes. In much the same way that I can imagine a world without circus animals or where bears are tapped for bile or any of the other futile cruelties we inflict on animals. It’s an easy question to answer because the morality it exposes is pale and jellied and it jingles like the pokies.

It’s hard to believe the makers of this documentary set out to solely explain what is happening in the great sea parks across the United States. From the very beginning a string of repentant trainers and whalenappers – crying, always crying – are paraded in front of the cameras, and there they speak with great regret of their participation in the industry.

This film is largely about redemption, and in that sense it is a profoundly American film, pushing the human interest element way out front where it has no business being. The last scene, in which a slew of former SeaWorld trainers, some of whom, by virtue of being trainers, are complicit in the torture and maltreatment of these animals, hop on a boat and go watch orcas in their natural habitat is nauseating.

I don’t care about these people, and I care even less about them knowing the extent to which they participated in the very industry that they are now so passionately railing against. I do, however, care about animals in captivity, and I’m not silly enough to imagine a world in which that doesn’t happen. Blackfish, however, having won its case by filming and pointing at the outrages, seems uninterested in unpacking the issue any further.

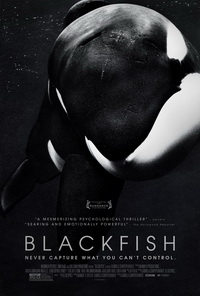

There are other missteps. “Blackfish,” is what certain First Nation’s people call orcas, and that’s all you will EVER learn about the cultural history of these animals in this documentary. It’s a throwaway line that helps explain where the documentary got its title, and it genuinely smacks of tokenism.

The conversation about how animals in captivity are treated, handled and ultimately disposed of after they’re done entertaining us is an important one. The manner in which director Gabriela Cowperthwaite uses Blackfish to address this certainly makes one reach for the tissues and starts to raise awareness, but ultimately it’s a vehicle to wash away the sins of people sobbing against the backdrop of depressed animals.

Edited by ES.

Reviewed on Wednesday, 22 January 2014