If you’ve read anything about The White Ribbon, perhaps in anticipation of the film, you would have come across the Q&A with director, Michael Haneke. In it, Haneke explains why he chose as a setting a village in Northern Germany prior to World War I. I will reprint it, because it is instructive in understanding this film.

Why do people follow an ideology? German fascism is the best-known example of ideological delusion.

The grown-ups of 1933 and 1945 were children in the years prior to World War I. What made them susceptible to following political Pied Pipers? My film doesn’t attempt to explain German fascism. It explores the psychological preconditions of its adherents. What in people’s upbringing makes them willing to surrender their responsibilities? What in their upbringing makes them hate?

The village in question is subject to a bizarre and increasingly disturbing series of events. The village doctor being knocked off his horse by a hidden wire and injured severely becomes the first act of tyranny – and it can only be described as such – in a series of tyrannies that befall the village.

The movie radiates out of this first transgression. We are introduced to the children of the village – children who have a strange tendency to show up expressing rather insincere concern following some of the tragic events that take place. They are responsible – seemingly, for it’s never quite confirmed – for some of the more overt crimes: a barn is torched, the midwife’s son, a disabled boy, is severely beaten, etc.

The crimes committed by the children have a religious taint, a sense of retribution. Of course, in light of Haneke’s comments regarding the disparity between the life of Christ and the doctrines of the churches that have come to worship him, it makes sense that at the centre of village life is strict, unbending religion, directed by the local pastor – a cold, sanctimonious man, whose strident morality is more destructive than not.

Some of the tyrannies are more ingrained, more massaged into the fabric of society. It is the pastor, after all, that ties the eponymous ribbon onto two of his children as a reminder of their absent purity. It is the pastor that ties one of his sons to his bed at night to prevent him masturbating. And, finally, it is in retribution for the some or other of the pastor’s actions that his eldest daughter – the undeclared leader of the gang – kills his beloved pet bird with a pair of scissors. As Haneke comments, “The psychological wounds inflicted on [children] can be repressed for a time, but everything that sleeps reawakens one day.”

The White Ribbon is a bleak, traumatising film. The words that the doctor, having returned from receiving medical care, directs at the midwife, his lover, are actually so cruel as to be distressing. As is the scene when a farmer’s son – responsible for destroying his father’s livelihood – enters a barn to find that his father has hanged himself.

The White Ribbon, filmed in crisp, beautiful black & white, is a pleasure to watch. It offers no answers, though, save for an attempt at psychological and historical context: “I think I must tell of the strange events that occurred in our village,” says the narrator. “They could perhaps clarify some things that happened in this country.”

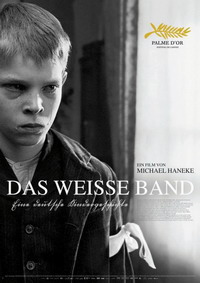

The White Ribbon

Reviewed on Tuesday, 25 May 2010